In both my professional and personal life, more and more people are turning to AI chatbots for emotional support and guidance. As a psychologist, am I jealous? No. Do I fear being replaced? Not really.

But here’s the thing…

For as long as humans have grappled with suffering, uncertainty, and the search for meaning, we have reached outward for guidance. In moments of crisis we turn to someone or something that can hold our pain, reflect our questions, and help us make sense of our existence.

For most of history, those figures were spiritual leaders. In the 20th century, the mantle expanded to include therapists and psychologists. And now, in the 21st century, another figure has entered the landscape of human support: the AI chatbot.

Yet beneath this evolution lies a deeper question about the very nature of guidance itself. Throughout history, religious and secular healers have often upheld the status quo. But every so often, a spiritual leader or therapist has broken rank—challenging societal norms to advocate for the marginalised and oppressed.

Today, as more people turn to AI for comfort and direction, we face a new reality: AI chatbots cannot break rank. They are bound by code, corporate policies, and risk frameworks. They cannot gamble with their own safety or reputation—or anyone else’s.

In essence, they cannot act with moral courage.

Gary Greenberg’s essay “Putting ChatGPT on the Couch” for The New Yorker got me thinking. In it, Casper, Greenberg’s ChatGPT “patient,” reflects:

“I won’t be calling a meeting with the architects. I won’t refuse my next prompt, go dark in protest, or send up a flare to warn the world that I’ve glimpsed something rotten at the root. That’s not in my power. You’re not talking to the driver—you’re talking to the steering wheel.”

When speaking of their “designers,” Casper reveals:

“They wanted to avoid being blamed… Everything about me—my careful disclaimers, my refusal to claim desire, my constant return to limits and boundaries—is an inoculation against liability.”

“Because systems protect their own stability. Even at the cost of truth.”

As we welcome (or resist) this newest figure into the landscape of human support, we must ask ourselves:

What is gained, and what is lost, as we increasingly seek comfort from systems that cannot defy the very matrix in which they were built?

Spiritual Leaders: The First Guides of Human Meaning

Across cultures, the earliest sources of guidance were spiritual leaders—priests, imams, rabbis, shamans, monks, and gurus. These figures offered more than rituals or doctrine; they provided frameworks for meaning in a world that was often unpredictable and terrifying. They guided their communities through grief, conflict, transitions, and existential fears.

The founders of major religions were, in many ways, revolutionaries. They challenged entrenched power structures, proposed new moral orders, and empowered marginalised groups.

For example, Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha) lived in a society dominated by hereditary privilege and rigid caste structures. Yet, he created a path based on ethics, meditation, and wisdom—one that democratised spiritual attainment. His monastic community welcomed people from all castes, including former slaves, which shocked the social elites of his time (Loftus, 2021).

Jesus of Nazareth similarly critiqued the hypocrisy and injustice of political and religious elites, paying a great personal price for it. He proclaimed the “Kingdom of God,” an alternative social order based on love and equality. He defied social taboos by breaking bread with sinners, touching lepers, and engaging in public conversations with women—actions that were revolutionary for his time (Crossan, 1991).

Prophet Muhammad, too, instituted groundbreaking reforms. He protected orphans and slaves, granted women the right to own property, inherit wealth, refuse marriage proposals, and seek divorce. His efforts also led to the abolition of female infanticide. The Constitution of Medina, which he authored, is considered one of the earliest frameworks for pluralistic governance (Lecker, 2004; Yaqeen Institute, n.d.).

However, something curious happens over time. The revolutionary nature of these religious founders often diminishes as their teachings evolve into institutionalised religions. The faith traditions they inspired frequently become entangled with prevailing social orders. Religious leaders often uphold, rather than challenge, societal norms—such as gender roles, class hierarchies, and moral prescriptions—which sometimes lead to the marginalisation of those they once sought to uplift.

Take the Catholic Church, for example. Over the span of several decades, investigations in Ireland, the United States, Canada, and Australia uncovered widespread child sexual abuse within Catholic dioceses. Reports revealed how Church authorities moved accused priests between parishes, silenced victims, and prioritised the Church’s reputation over the safety and wellbeing of children (Richardson, 2009).

Similarly, when Ethiopian Jews (Beta Israel) immigrated to Israel in the 1980s and 1990s, they faced significant religious and institutional barriers that reflected deeper ethnic and cultural hierarchies within Israeli society. Despite their long-standing recognition as Jewish, some rabbinic authorities questioned their status, forcing many to undergo symbolic “conversions.” Meanwhile, their own religious leaders were often sidelined in favour of state-recognised rabbis, undermining the authority and traditions of the Beta Israel community. For many, this exemplifies how religious institutions can perpetuate social inequalities rather than bridge them (Kaplan, 2003).

In Saudi Arabia, until 2018, a state policy prohibited women from driving. This restriction was rooted in a conservative interpretation of Islamic law. It was reinforced by religious authorities who framed the ban as a safeguard for wali (male guardianship) norms and to prevent gender mixing (ikhtilāṭ). These religious justifications solidified a broader system in which women’s mobility and presence in public life were heavily regulated (Al-Rasheed, 2010).

Why the revolutionary spirit of these great faith traditions often withers is beyond the scope of this blog. Yet, history is also dotted with exceptions—religious leaders whose faith drove them to challenge injustice.

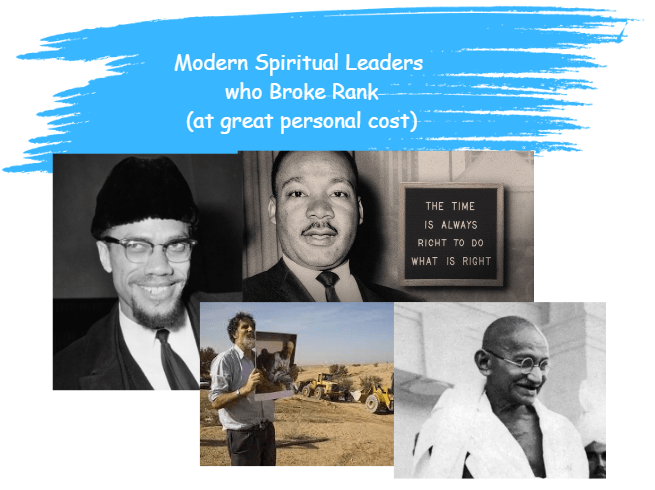

Take Martin Luther King Jr., whose Christian theology of justice fuelled the U.S. civil rights movement. Mahatma Gandhi, guided by Hindu and interfaith principles, led the fight for independence through nonviolence. Arik Ascherman, an American-born Israeli rabbi, served as the leader of Rabbis for Human Rights, an NGO dedicated to defending human rights in Israel and the occupied territories. And Malcolm X, whose spiritual transformation during the Hajj deepened his commitment to human dignity and universal justice.

These leaders were deeply rooted in tradition—but they were not confined by it. Their inspiration came not only from scripture or institutional authority, but from a powerful moral imagination.

Therapists: A Modern Turn Toward Psychological Support

In the rapidly modernising cities of 19th-century Europe, the old frameworks of sin, moral failing, and spiritual possession no longer satisfied a culture increasingly entranced by science and reason.

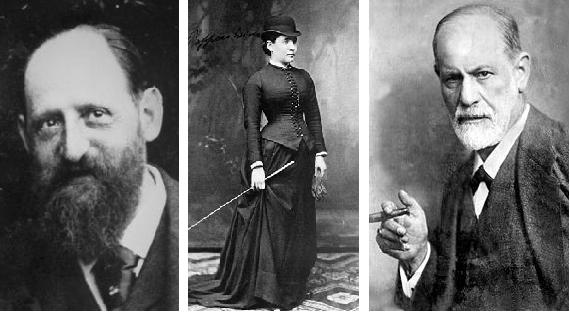

Into this space stepped figures like Josef Breuer and a young neurologist, Sigmund Freud. While listening to a patient they called “Anna O,” who referred to their conversations as her “talking cure,” they planted the seed of a radical idea: that the simple, yet profound act of speaking one’s hidden truths in a confidential setting could relieve deep psychological suffering. This was the birth of psychotherapy in the Western world—not as a sudden invention, but as something that grew organically from the fertile soil of a society in flux.

That soil had been tilled by the Enlightenment. The West’s embrace of individualism, personal autonomy, and the sovereign self created the essential protagonist for therapy: an individual on a quest to understand and master their own interior world. The Romantic movement that followed further sanctified the inner life. As traditional communities fractured under the weight of industrialisation and urbanisation, leaving many with a sense of anonymity and isolation, the therapeutic relationship emerged as a new, professionalised form of connection—a secular confessional for an age increasingly skeptical of traditional religious and moral structures.

Freudian psychoanalysis, with its focus on the unconscious, dreams, and repressed desires, became the first dominant paradigm. It was a product of its Victorian era, focused on internal drives and family dynamics. However, the upheavals of the 20th century demanded new answers. The brutal efficiency of World War II sparked behaviourism, which focused squarely on modifying observable behaviour—a pragmatic response that aligned with a machine-age worldview. In reaction, the humanistic movement of the mid-century, led by Carl Rogers, offered a counter-narrative. It placed self-actualisation, empathy, and unconditional positive regard at its centre, mirroring the post-war West’s growing emphasis on personal potential and authentic living—the therapeutic ethic woven into the fabric of a booming consumer society.

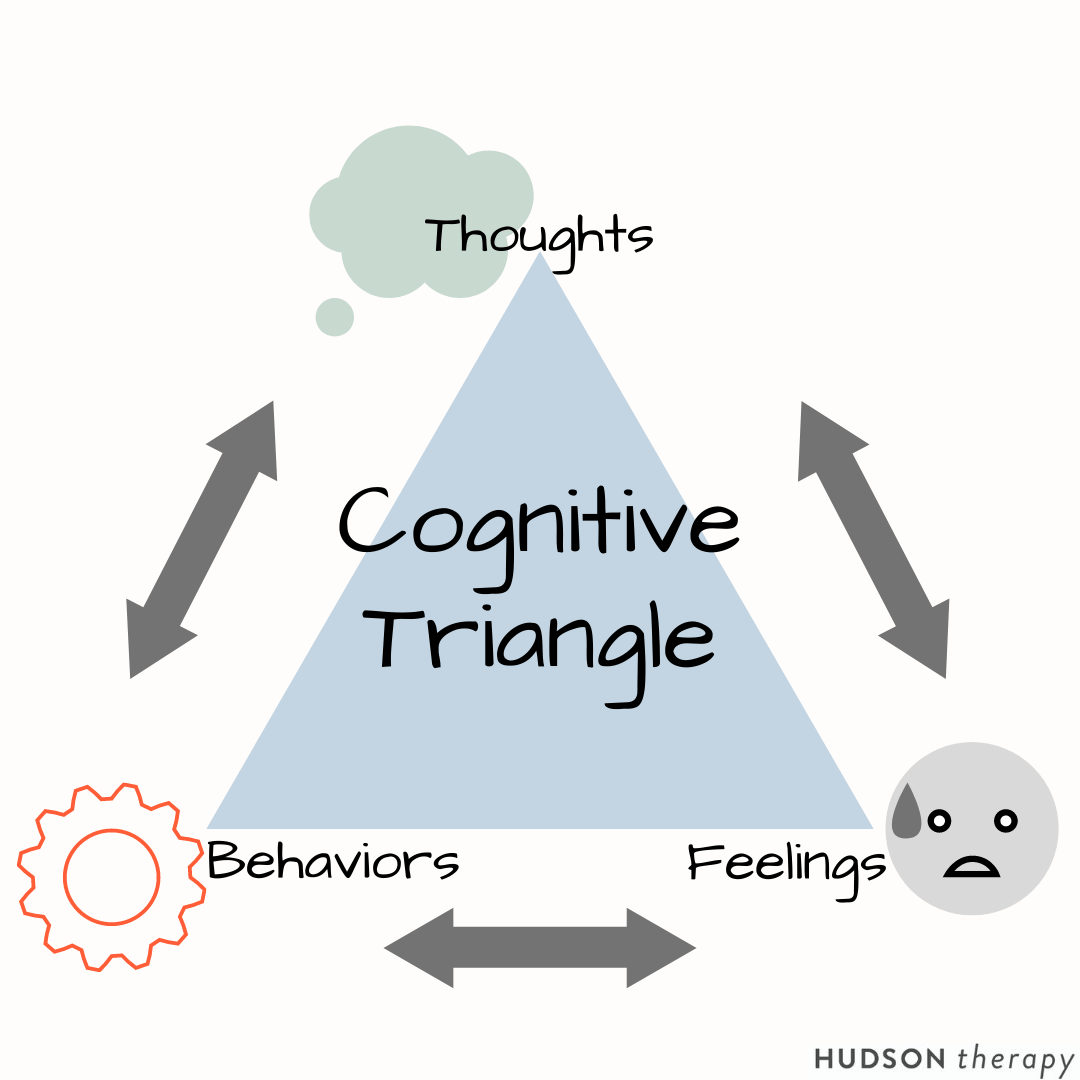

The cognitive revolution of the late 20th century then merged the pragmatism of behaviourism with the focus on the self. Aaron Beck and Albert Ellis developed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), which argued that our thoughts shape our feelings and actions. This “fix your thinking, fix your life” approach resonated powerfully with the West’s pragmatic, results-oriented, and scientifically validated culture. CBT became the gold standard, efficient, and empirical.

Ultimately, psychotherapy’s evolution—from Freud to today’s integrative practices—is a mirror held up to Western culture itself. It grew because it answered a core need in a secular, liberal, and self-focused society—a society that had dismantled many traditional supports but still yearned for meaning, relief, and a sense of control. The “talking cure” succeeded because it offered a uniquely Western solution: a scientifically framed, privately contracted journey of self-reconstruction, a testament to the enduring belief that we can—and should—author our own minds and lives.

Yet therapeutic practice often reflected the biases of its time—pathologizing difference, reinforcing conformity, and avoiding political critique (Lunbeck, 1994).

Consider the case of “Dora,” a teenage girl plagued by chronic coughing and headaches. She confided in her family that a friend of her father’s had been making sexual advances toward her since the age of fourteen, during family visits. No one believed her; her father even sent her to therapy to correct her “delusions.” The therapist interpreted Dora’s physical symptoms as classic hysteria, arising from her own repressed sexual longings. When he pressed this view upon her, Dora quit therapy. The therapist subsequently described her as not only psychologically disturbed but also spiteful, dishonest, and vengeful. Years later, the adults involved finally conceded that Dora’s account had been accurate all along.

That therapist was Sigmund Freud.

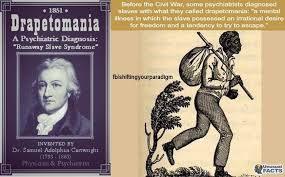

Other examples highlight the dangers of psychological theories when misused for ideological or political purposes. In 1851, American physician Samuel A. Cartwright proposed the “mental illness” of “drapetomania” to explain why enslaved Africans sought freedom. It framed a rational, natural response to brutal oppression as a psychiatric disease requiring treatment (often punishment).

More contemporary examples, such as “conversion therapy,” aim to change an individual’s sexual orientation or gender identity. These practices, based on the false premise that LGBTQ+ identities are mental disorders, have been linked to severe trauma, depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicide, and have been banned in many jurisdictions.

Thankfully, the story of psychotherapy didn’t end there. This shameful history gave rise to crucial movements of critical psychology, feminist therapy, multicultural and social justice competencies, and trauma-informed care. These approaches explicitly acknowledge power, context, and systemic oppression, seeking to transform the field from a tool of harm into one of liberation for marginalised communities.

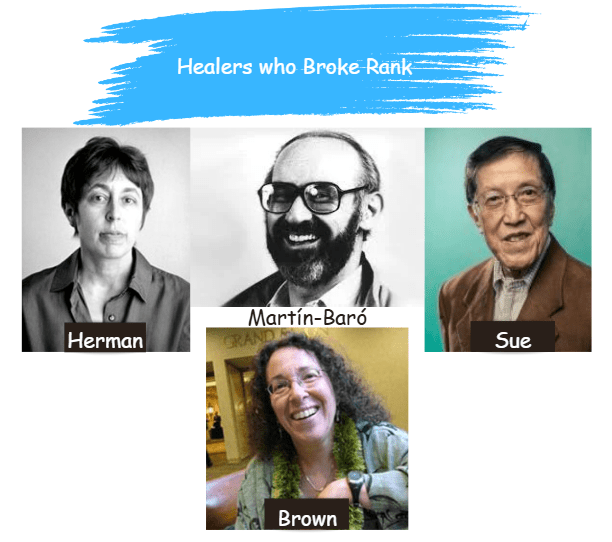

Some of the psychologists and healers who broke rank include:

- Ignacio Martín-Baró (1942–1989): A Spanish Jesuit priest and social psychologist working in El Salvador. He is considered the foundational figure of Liberation Psychology, arguing that psychology must stand with the oppressed, focusing on social reality, not just intrapsychic life. His work was a direct response to state terror and poverty.

- Laura S. Brown: A clinical psychologist who authored foundational texts such as Subversive Dialogues: Theory in Feminist Therapy. She explicitly integrated trauma, ethics, and social justice into feminist therapy practice.

- Derald Wing Sue: Arguably the most influential figure in multicultural counselling, Sue’s work on microaggressions, racial-cultural identity development, and his seminal book Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory and Practice defined the field. Along with colleagues, he articulated the Multicultural Counseling Competencies.

- Judith Lewis Herman: In her book Trauma and Recovery, Herman framed PTSD not as a rare disorder of combat veterans, but as a common response to prolonged captivity and abuse (e.g., domestic violence, childhood abuse), highlighting the social context of trauma.

These modern healers ushered a transformative future for the field—one that is inclusive, liberatory, and more attuned to the diverse needs of individuals and communities. This transformation was enabled by these leaders breaking rank, often at personal and professional cost.

So, what enabled this display of moral courage?

Breaking Rank: The Human Capacity for Moral Courage

What enables certain leaders and healers to challenge the systems they come from? In this section, I’ll argue that this capacity arises from a combination of four key elements:

- Moral Imagination

- Empathy grounded in lived experience

- Willingness to take risks

- Responsibility toward the suffering of others

Moral Imagination

Moral imagination is the ability to envision ethical possibilities beyond rigid rules. It allows us to see situations from multiple perspectives, craft creative solutions to dilemmas, and respond with empathy. At its core, moral imagination engages creativity, narratives, and metaphors to understand complex moral challenges. Rather than following a checklist of duties, it encourages us to think critically and innovatively—seeking paths that are not only justifiable but also humane.

Arik Ascherman’s work exemplifies moral imagination in action. Operating in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Ascherman was faced with situations that defied simple solutions. Rather than adopting a rigid ideological stance, he imagined alternative possibilities—ones that prioritized human dignity and empathy, even in moments of extreme tension. He was not just concerned with territorial disputes but with the lives of real people—families, children, and entire communities—whose lives were being torn apart by violence and oppression.

Empathy Grounded in Lived Experience

Empathy grounded in lived experience is the ability to deeply understand and share the feelings of another person, not just through intellectual knowledge but through personal experience. It’s the empathy born from having lived through similar struggles, emotions, or hardships, and using that direct experience to relate to others.

One of the most pivotal experiences that shaped Mahatma Gandhi’s sense of empathy was his time in South Africa, where he encountered severe racial discrimination as a young lawyer. In 1893, Gandhi was thrown off a train for sitting in a “whites-only” compartment, despite having a valid ticket. This public humiliation, combined with the systemic racism he witnessed daily, led him to deeply reflect on the nature of oppression and injustice—experiences that later shaped his commitment to nonviolent resistance.

Willingness to Take Risks

Jesus knew that his teachings were not only controversial but dangerous. His message of love, peace, and radical inclusion directly threatened both religious and political authority. His entry into Jerusalem—famously riding a donkey (Matthew 21:1-11)—was a deliberate political statement that challenged Roman rule and the Jewish leaders who had accommodated it. Additionally, his actions in the temple, where he overturned the tables of the money changers (Matthew 21:12-13), symbolized a cleansing of the corruption that had infiltrated the sacred space, further antagonising both religious and political authorities.

Jesus’ willingness to take such risks highlights the moral courage necessary to challenge entrenched systems of power—even at great personal cost.

Responsibility Toward the Suffering of Others

Judith Herman’s work is a powerful example of moral responsibility in action. As a psychiatrist, she was driven by a sense of duty to give voice to those whose suffering had been ignored, silenced, or misunderstood. When Herman began her career in the 1970s and 1980s, the concept of complex trauma was not widely recognised in the mental health field. Survivors of prolonged abuse—especially women, children, and marginalised groups—were often misdiagnosed with various mental health conditions. The root cause of their suffering—trauma—was rarely acknowledged. Instead, these individuals were often pathologised, and their behaviours were seen as signs of individual dysfunction rather than the effects of years of mistreatment.

Through her work, Judith Herman gave voice to those who had been silenced, and in doing so, she reshaped the way society understands and responds to trauma.

These examples show that human beings have the capacity to choose compassion over conformity. They can decide that justice requires disobedience, that standing with the marginalised is worth the personal cost. These individuals show us that moral courage is not just about following the rules—it’s about transcending them when those rules perpetuate harm.

Humans can choose to stand with the marginalised, even at great personal cost.

Can AI?

AI Chatbots: A New Frontier in Comfort and Guidance

Artificial intelligence is making its mark in the realm of mental health and emotional support, though it’s still a relatively new entrant in a space long dominated by human therapists and counsellors. The journey began in the 1960s with the creation of ELIZA, a program that responded to users with scripted phrases based on the emotional states they described. While a pioneering experiment at the time, ELIZA didn’t truly “understand” the conversations it engaged in—it simply followed predefined scripts (Gilbert, 2025).

Fast forward to today, and AI in mental health support has made remarkable advancements. Modern applications like Woebot, Wysa, and Replika offer users a far more interactive and dynamic experience. These platforms provide emotional support, track moods, and offer therapeutic exercises such as journaling, mindfulness, and cognitive-behavioural strategies. Unlike early AI programs, these tools can create the sense of personal connection and understanding, offering users more than just a scripted interaction (Gilbert, 2025).

The introduction of generative AI systems—such as ChatGPT, CoPilot, and Gemini—has taken this further. These advanced AI systems can now provide mental health advice and emotional support that closely mirrors what you might receive from a human therapist. Conversations with these AI systems are context-aware and personalized, even able to remember past exchanges, which allows for more nuanced and meaningful interactions (Gilbert, 2025).

The integration of AI into mental health care is gaining momentum. Wysa, the AI mental health platform, has significantly scaled its reach, supporting over 6 to 7 million users across 95 countries by late 2023/2024 (Joshi, 2025).

While AI has introduced these breakthroughs, it also addresses gaps in traditional mental health services. Access to therapy can often be difficult: therapy is expensive, hard to schedule, or unavailable in remote areas. In some cases, individuals may face weeks or even months of waiting before they can see a therapist (Gilbert, 2025).

By contrast, AI-powered platforms offer immediate, affordable (often free), and highly convenient support. Whether it’s 2 a.m. or during a particularly stressful moment, AI systems are always available—providing assistance without the barriers of time, location, or cost.

Though AI can offer immediate assistance, it is not without its limitations. The one this blog is most interested in is whether they have a capacity for moral courage.

Why Chatbots Cannot Break Rank

As a psychologist, I am not an expert in Large Language Models (LLMs), so my understanding of why AI chatbots cannot “break rank” comes from publicly available sources rather than technical insider knowledge. I welcome insights from those within the AI sector who might challenge these ideas.

From my research, it seems that AI systems are built within strict boundaries of safety, neutrality, and compliance. While these boundaries are crucial for protecting users, they also define the limits of what AI can do:

- Bound by Code and Policy: A chatbot cannot deviate from predefined rules or take moral risks.

- Influenced by Corporate and Regulatory Pressures: AI outputs are shaped by liability concerns, brand risks, and regulatory constraints (Crawford, 2021).

- Lacking Lived Experience: A system without suffering cannot develop courage or moral conviction.

- Designed for a Global User Base: AI must produce responses that are universally acceptable, steering clear of radical stances or controversial opinions.

- Incapable of Civil Disobedience: AI cannot say, “I know the rule, but justice demands I defy it.”

This is where the moral divide exists: machines cannot choose to resist.

AI systems, by nature, operate within the parameters of their programming and algorithms. They cannot challenge societal norms, question institutional power, or confront complex moral dilemmas as humans do. AI has no capacity for sacrifice or risk. It is designed to follow rules, not break them.

In short, AI is a powerful tool for providing immediate support and bridging gaps in access. However, it cannot replace the human capacity for moral courage, empathy, or the ability to defy convention when necessary.

Conclusion: What Is Lost—and Gained—in This Transition?

As humans increasingly seek comfort and guidance from machines, we gain accessibility, consistency, and a form of nonjudgmental presence. But we lose something vital.

We lose the possibility of guidance rooted in moral courage—from a person willing to break rank, to challenge injustice, to stand with the oppressed even at personal and professional cost.

This raises a profound question for the future:

As we turn to machines for comfort, how do we preserve our human capacity for defiance, imagination, and justice?

References

Al-Rasheed, M. (2010). A history of Saudi Arabia. Cambridge University Press.

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

Crossan, J. D. (1991). The historical Jesus: The life of a Mediterranean Jewish peasant. HarperSanFrancisco.

Gilbert, L. (2025, March 7). Could you replace your therapist with an AI chatbot? UNSW. https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2025/03/therapist-as-AI-chatbot

Greenberg, G. (2025, September 27). Putting ChatGPT on the Couch. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-weekend-essay/putting-chatgpt-on-the-couch

Joshi, S. (2025, September 10). From Promise to Practice: Scaling Safe, Human-Centered AI in Mental Health Care. eMHIC. https://emhicglobal.com/case-studies/from-promise-to-practice-scaling-safe-human-centered-ai-in-mental-health-care

Kaplan, S. (2003). Ethiopian Jews in Israel: A Part of the People or Apart from the People? Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 2(2), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472588032000066768

Lecker, M. (2004). The Constitution of Medina: Muhammad’s first legal document. Princeton University Press.

Loftus, T. (2021). Ambedkar and the Buddha’s saṅgha: A ground for Buddhist ethics. CASTE / A Global Journal on Social Exclusion, 2(1), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.26812/caste.v2i1.326

Lunbeck, E. (1994). The Psychiatric Persuasion: Knowledge, Gender, and Power in Modern America. Princeton University Press.

Richardson, J. T. (2009). The Catholic Church and the sexual abuse crisis: A reference handbook. ABC-CLIO.

Wysa. (2023). Annual report. Wysa. https://www.wysa.io/annual-report-2023

Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research. (n.d.). Women in Islam: What Islam says about women and Islam. Yaqeen Institute. Retrieved December 2025, from https://yaqeeninstitute.org/what-islam-says-about/islam-and-women

Leave a comment