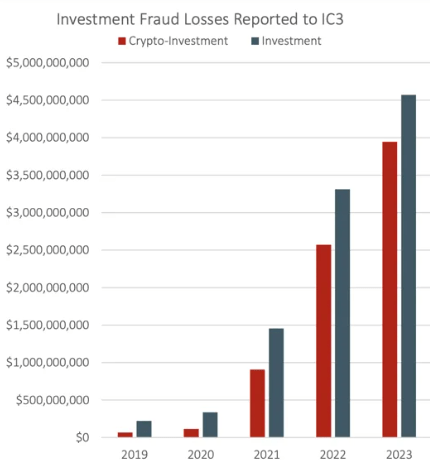

Ever since Bitcoin’s 2017 price surge, the astronomical gains and monumental losses characterising cryptocurrencies (crypto) have captured the world’s attention. These losses are not always due to run-of-the-mill market trends. According to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), crypto-related investment fraud in 2023 totalled a staggering $3.96 billion, representing a 53% increase from 2022.

Australians are by no means spared. According to the Australian Federal Police (2024), we lost $180 million in crypto investment scams over 12 months.

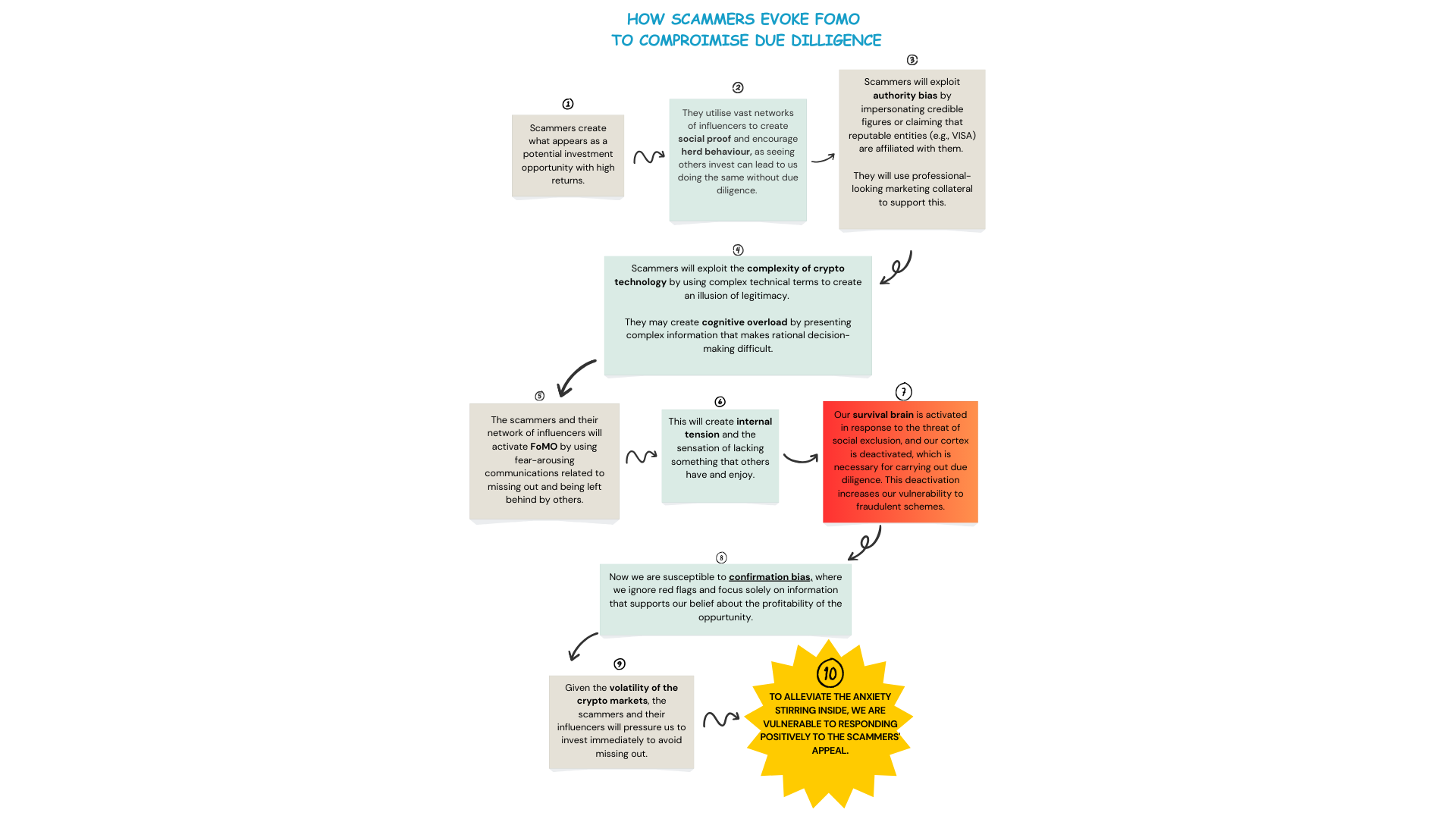

These scams share similarities to traditional fraud. However, my research suggests that Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) in crypto contexts is particularly pervasive. Scammers employ a range of sophisticated tactics to create a sense of FoMO and a fabricated sense of urgency.

The fear of missing out on a financial opportunity is at the foundation of the scam. However, scammers skilfully introduce a social exclusion factor: everyone is jumping on board with this opportunity, and if you do not act now, you will be left behind. This activates our primal survival instincts related to social exclusion, the nature of which undermines our ability to conduct due diligence.

Given the scarcity of research on the psychological dimension of crypto scams, the purpose of this blog is to spark conversation. This dialogue allows us to become more aware of the scammers’ tactics and the neurobiological states they seek to evoke.

I aim to achieve this by:

- Explaining crypto scams, particularly those where FoMO is a pervasive factor (e.g. rug pulls)

- Exploring FoMO from an evolutionary perspective

- Unpacking the neurobiological response to FoMO and how it undermines due diligence in crypto investment decision-making

I hope that this awareness decreases our vulnerability to scammers’ tactics when navigating the crypto world.

What are crypto scams, and how do they work?

The unique features of crypto (decentralisation and privacy) have ironically been exploited to carry out various scams. These scams use a combination of psychological tactics and technical expertise. Even with improvements in cybersecurity and protective measures, people’s vulnerability to manipulation remains a key factor (Perdana & Jiow, 2024).

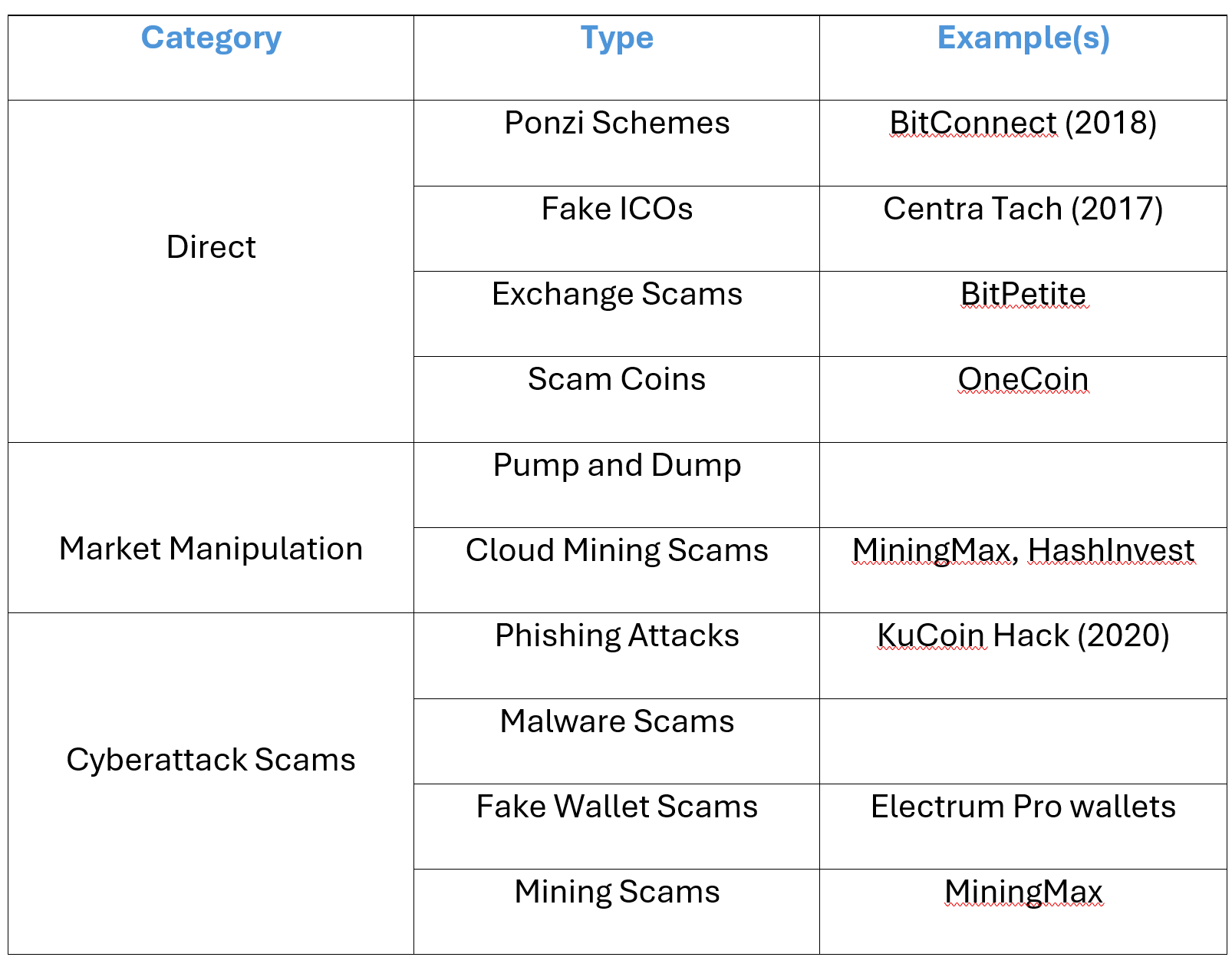

Perdana and Jiow (2024) provide a comprehensive classification of crypto scams, categorising them into the following:

The introduction of smart contracts and decentralised finance (DeFi) created new opportunities for scammers. They exploited these innovative technologies to create more sophisticated scams, such as rug pulls (Perdana & Jiow, 2024).

A rug pull occurs when crypto project developers suddenly withdraw all the funds (i.e., drain liquidity) from the project, essentially pulling the rug out from under investors who are left with worthless tokens (Perdana & Jiow, 2024).

Industry Factors Creating Vulnerability to Crypto Scams

Several industry factors contribute to the vulnerability to and prevalence of crypto scams. They include:

Nature of crypto projects and assets: The value of many cryptos is extremely low, making it easier to manipulate their prices. Additionally, recently created crypto projects or assets, mainly meme coins, often rely on a constructed narrative rather than tangible value. They are, therefore, highly speculative without an established track record.

Technological complexity: Many people struggle to understand blockchain technology due to its inherent complexity. This creates vulnerability to scammers.

Lack of regulation: Regulation is lacking or non-existent in most jurisdictions. Even where regulation exists, things like meme coins often escape regulatory oversight.

Anonymity: Transactions on a blockchain are not directly linked to a person’s real-world identity. Instead, they are associated with digital wallets, which are anonymous strings of numbers and letters. It is possible to track transactions and identify which wallets are involved. However, determining who owns those wallets is difficult. Additional information must connect the wallets to a specific individual.

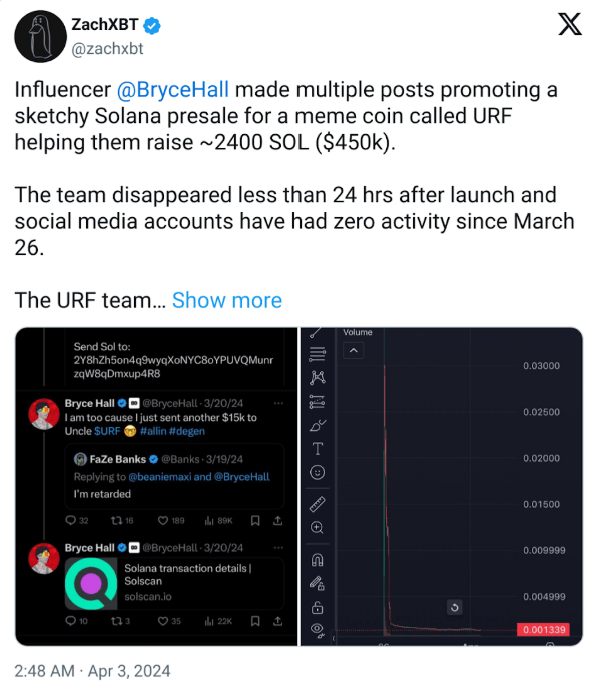

Sophisticated marketing, including orchestrated social media hype: Given the potential returns, scammers spare no expense on sophisticated, multi-pronged marketing strategies. They utilise networks of influences and even celebrities to drive social media hype. They may develop professional-looking websites and marketing materials. They may even pose as analysts from reputable financial institutions.

High Return Potential and FoMO: Sophisticated market techniques and the promise of high returns can trigger FoMO. A perception is purposefully created that everyone is jumping on board with this new coin, leaving you behind if you do not invest. This compromises an investor’s judgment, making them more susceptible to risky and fraudulent offers.

Types of Crypto Scams Exploiting FoMO

While FoMO can be evoked in any type of crypto scam, there are specific scams where it is more central to the scammers’ strategy, including:

Rug Pulls: Developers create a meme coin and employ aggressive marketing tactics across social media platforms. They lure investors with claims of the coin’s innovative features, functionalities, or real-world applications. Once investors contribute significant funds, lured by FoMO, the developers disappear, taking the investors’ money with them.

Fake Initial Coin Offering (ICO): A legitimate ICO aims to release a new coin to the public. The expectation is that developers will use the funds to support the coin’s further development. This, by default, enhances its value. A fake ICO involves launching a non-existent coin. The developers then vanish with the proceeds from the ICO.

Crypto Ponzi schemes: These operate similarly to traditional Ponzi schemes, offering high returns based on new investors injecting capital. Investors are initially led to believe that legitimate crypto development is fuelling investment returns. Then, those behind the scheme disappear with all their funds.

Pump-and-dump schemes: Scammers employ various tactics to artificially pump the price of a digital asset. Once the price is inflated, the scammer immediately dumps (i.e. sells) their tokens. The rapid increase in the token supply causes its price to fall, but not before the scammer collects a profit.

As mentioned above, crypto projects and assets are primarily speculative and dependent on socially constructed opinions. Accordingly, potential investors heavily rely on social media and online platforms to get investment information. In this crypto information ecosystem, potential investors may fall prey to certain strategies. These strategies are designed to evoke FoMO and an artificial sense of urgency (Perdana & Jiow, 2024).

Introducing FoMO from an evolutionary perspective

The advent of social media means people are continuously exposed to what others are doing. For some, this creates uncertainty about how they are living their lives, their status and their achievements.

The term “Fear of Missing Out” (FoMO) was introduced in 2004 and popularised in 2010 to describe this phenomenon. It is defined as a:

pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent. (Przybylski, et al., 2013)

FoMO involves two processes:

1) the perception of missing out

2) a compulsive behaviour to stay continually connected with what others are doing.

It can present as:

- a fleeting feeling (e.g. when scrolling through social media)

- a lasting disposition

- or a mindset that causes a deep sense of social inadequacy, isolation, or overwhelming anger (Gupta & Sharma, 2021).

While FoMO may feel like a recent social phenomenon, humans have always experienced distress when missing out on opportunities to connect. This includes chances to connect with potential partners. Social media likely intensifies the experience, given the saturation of curated portrayals of other people’s lives.

Davis, Albert, and Arnocky (2023) argue that FoMO originates in our evolution, triggering primal survival instincts. This is important in relation to vulnerability to crypto scams, but more on that later!

Evidence suggests that humans evolved in the context of small, nomadic hunter-gatherer communities where forming and maintaining social bonds were essential for survival and reproduction.

Being excluded from social events would have harmed early humans’ survival. Failing to participate in these events may have affected their reproductive success. Therefore, humans are evolutionarily primed to experience anxiety when social bonds are threatened or harmed, in addition to when we are purposely left out of meaningful social activities.

The adaptive function of this anxiety is to alert us to the threat. It allows us to overcome the risks to survival and reproductive success.

Like anxiety, FoMO may be a psychological adaptation that seeks to protect us from social exclusion and encourage social inclusion. Davis, Albert, and Arnocky (2023) suggest:

If so, then the expression of FoMO should orient individuals toward evolutionarily relevant social resources, such as social status, and prompt compensatory behavior to accrue those resources.

However, one may ask…

if FoMO is adaptive, why is it associated with poor mental health outcomes and problematic social media use?

Davis, Albert, and Arnocky (2023) argue that social media and, by extension, FoMO, represent an evolutionary mismatch.

Social media is believed to cause a mismatch between how our brains evolved and how we interact with modern technology. Humans evolved to thrive in small social groups, where belonging and social monitoring were important for survival. However, social media platforms exploit these natural tendencies, which can lead to negative mental health effects. In other words, social media uses our need for connection in ways that can be harmful. So, while our internal neurobiological responses to FoMO are perfectly natural, they are triggered by an unnatural (and some would argue exploitative) context. Hence the problematic psychosocial impacts.

Survival Brain vs. Thriving Brain: The Neurobiology of FoMO

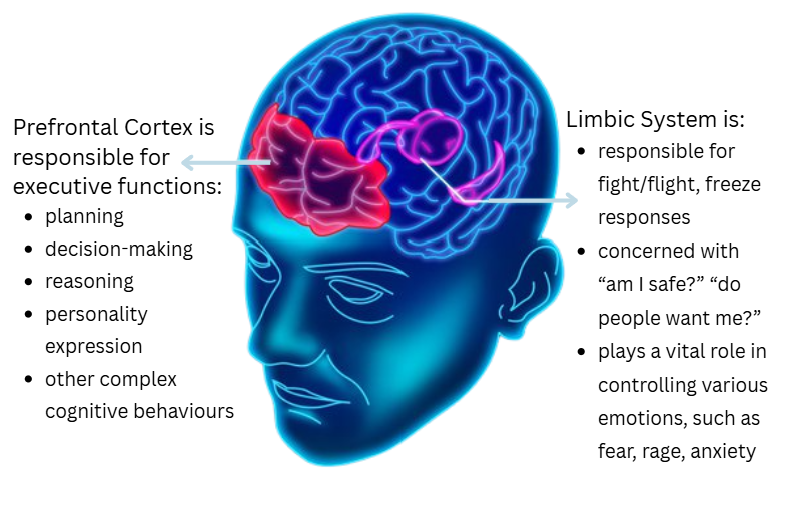

Humans have evolved ways to respond to threats (perceived or actual) to keep us safe. When a threat has been identified, various parts of our brain, particularly our limbic structures, work in conjunction with our nervous system and body to orient us towards overcoming that threat. This promotes our survival. For example, your heart rate increases to pump oxygen-rich blood to your muscles, thereby improving their performance. Your pupils dilate, allowing more light to enter your eyes, enhancing your vision.

When humans feel safe, our brains work in conjunction with our nervous systems and bodies to prime us for learning, exploration, and connection. We have increased access to certain parts of our brain, specifically the frontal cortex, which enables abstract reasoning, critical thinking, creativity, and empathy.

Whenever humans are confronted with a threat, the limbic system becomes dominant, overriding the prefrontal cortex. We have evolved this way to ensure we are primed to overcome immediate threats to our safety. This works perfectly with physical threats. However, there are times we may experience a mismatch between a modern threat scenario and our evolutionary fear responses.

For example, we are sitting in a job interview. We begin to feel anxious. Our hearts beat, and we struggle to find the words to express ourselves. This fear response is undermining our ability to be successful in the interview!

This makes perfect sense. The limbic part of our brain has taken over. We now have limited access to the language and comprehension centers of our brain, located in the cortex. In this instance, a modern threat is mismatched to our evolutionary response to fear.

As discussed above, FoMO evokes a primal fear response related to being excluded from social groups and failing to participate in social events. The threat of social exclusion triggers a primal fear because, from an evolutionary perspective, it poses a direct threat to our survival and reproductive success.

In a crypto context, scammers are effective in evoking this fear state. They convey a sense that you are at risk of being left behind by the clan, who are all jumping on board with what will be the next Bitcoin or Ethereum. Given the volatility of the crypto market, a fake sense of urgency is created. So, if you do not act now, you will be left behind while the rest of the clan moves into this new stratosphere of crypto wealth and status. Not to mention sexual partners of their choosing.

That type of threat causes our survival brain to take over. In doing so, we are cut off from our frontal cortex or our thinking brain. This is particularly relevant to crypto investing. Whenever evolutionarily primed survival responses are activated, they cause the more evolved parts of our brain to go offline. These parts enable critical and analytical thinking, research, and consequential decision-making. The very mental processes that underpin due diligence.

Bringing it all together: FoMO and Crypto Scams

Max Jones, in an opinion piece for CryptoSlate, writes:

FOMO, or the fear of missing out, plays a major role in the success of rug pulls. Social media is a breeding ground for hype, where users can easily get caught up in the herd mentality. Scammers exploit this by creating a sense of urgency, urging investors to buy before they miss out on the next big thing. Fear and excitement cloud judgment, leading investors to make impulsive decisions without proper research.

Friederich et al. (2023) conducted five studies, including eight different experiments and discovered externally evoked FoMO:

- Influences consumers’ crypto investment decisions

- Leads consumers to repeated investment decisions, even if prior losses have been incurred.

They concluded that externally evoked FoMO can be a driving factor in the reduced processing of concerns and in making risky investment decisions, regardless of market conditions (e.g., bullish or bearish).

So, what’s next?

The complexity of crypto scamming, combined with the staggering losses, necessitates immediate action. The type of comprehensive response required to address this issue at multiple levels (e.g., regulatory, technical, cultural, etc.) is well beyond my area of expertise.

Having said that, scammers are clearly employing strategies that impact neurobiological states in potential victims. These strategies shut down the parts of our brain responsible for due diligence. It is this psychological dimension that warrants further investigation. Whatever measures are established to protect people from crypto scamming, they need to address the very human vulnerability to manipulation.

References

Australian Federal Police. (2024, August 28). AFP alerts Australians to common cryptocurrency investment scam tactics for Scams Awareness Week [Press Release]. https://www.afp.gov.au/news-centre/media-release/afp-alerts-australians-common-cryptocurrency-investment-scam-tactics

Davis, A. C., Albert, G., & Arnocky, S. (2024). The links between fear of missing out, status-seeking, intrasexual competition, sociosexuality, and social support. Current Research in Behavioural Sciences. Vol 4. 100096. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666518223000013

Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime Complaint Center (IC3). (2024, September 10). 2023 Cryptocurrency Fraud Report Released: Estimated losses with a nexus to cryptocurrency totaled more than $5.6 billion. https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2023-cryptocurrency-fraud-report-released

Friederich, F., Meyer, J-H., Matute, J., & Palau-Saumell, R. (2023). CRYPTO-MANIA: How fear-of-missing-out drives consumers’ (risky) investment decisions. Psychology & Marketing. 41, 1, pp. 102-117. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/mar.21906

Gupta, M., & Sharma, A. (2021). Fear of missing out: A brief overview of origin, theoretical underpinnings and relationship with mental health. World journal of clinical cases, 9(19), 4881–4889. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.4881

Jones, M. (2024, July 7). The Dark Side of the Memes: Rug pulls, FOMO, and the Dogefather effect. CryptoSlate. https://cryptoslate.com/the-dark-side-of-the-memes-rug-pulls-fomo-and-the-dogefather-effect/

Perdana, A. & Jiow, H. J. (2024). Crypto-Cognitive Exploitation: Integrating Cognitive, Social, and Technological perspectives on cryptocurrency fraud. Telematics and Informatics. 99. 102191. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0736585324000959

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R. & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, Emotional, and Behavioral Correlates of Fear of Missing Out. Computers in Human Behavior. 29. 1841-1848. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014.

Leave a comment